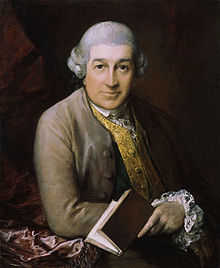

On David Garrick's Acting

The fame of the actor and theatrical manager David Garrick (1717–1779) was unsurpassed in his lifetime. Many tributes and descriptions point to the naturalness of his acting.

On the 19th of October 1741, David Garrick acted Richard the Third, for the first time, at the playhouse in Goodman's Fields. So many idle persons, under the title of gentlemen acting for their diversion, had exposed their incapacity at that theatre, and had so often disappointed the audiences, that no very large company was brought together to see the new performer. However, several of his own acquaintance, many of them person of good judgment, were assembled at the usual hour; though we may well believe that the greater part of the audience were stimulated rather by curiosity to see the event, than invited by any hopes of rational entertainment.

An actor, who, in the first display of his talents, undertakes a principal character, has generally, amongst other difficulties, the prejudices of the audience to struggle with, in favour of an established performer. Here, indeed, they were not insurmountable: Cibber, who had been much admired in Richard, had left the stage. Quin was the popular player; but his manner of heaving up his words, and his laboured action, prevented his being a favourite Richard.

Mr. Garrick's easy and familiar, yet forcible style in speaking and acting, at first threw the critics into some hesitation concerning the novelty as well as propriety of his manner. They had been long accustomed to an elevation of the voice, with a sudden mechanical depression of its tones, calculated to excite admiration, and to intrap applause. To the just modulation of the words, and concurring expression of the features from the genuine workings of nature, they had been strangers, at least for some time. But after he had gone through a variety of scenes, in which he gave evident proofs of consummate art, and perfect knowledge of character, their doubts were turned into surprise and astonishment, from which they relieved themselves by loud and reiterated applause. They were more especially charmed when the actor, after having thrown aside the hypocrite and politician, assumed the warrior and the hero. When news was brought to Richard, that the Duke of Buckingham was taken, Garrick's look and action, when he pronounced the words,

—Off with his head!

So much for Buckingham!

were so significant and important, from his visible enjoyment of the incident, that several loud shouts of approbation proclaimed the triumph of the actor and satisfaction of the audience. The death of Richard was accompanied with the loudest gratulations of applause.

For the first time in my life I was treated with the sight of Garrick in the character of Lothario; Quin played Horatio, Ryan Altamont, Mrs. Cibber Calista and Mrs. Pritchard condescended to the humble part of Lavinia. I enjoyed a good view of the stage from the front row of the gallery, and my attention was rivetted to the scene. I have the spectacle even now as it were before my eyes. Quin presented himself upon the rising of the curtain in a green velvet coat embroidered down the seams, an enormous full bottomed periwig, rolled stockings and high-heeled square-toed shoes: with very little variation of cadence, and in a deep full tone, accompanied by a sawing kind of action, which had more of the senate than of the stage in it, he rolled out his heroics with an air of dignified indifference, that seemed to disdain the plaudits, that were bestowed upon him. Mrs. Cibber in a key, high-pitched but sweet withal, sung or rather recitatived Rowe's harmonious strain, something in the manner of the Improvisatories: it was so extremely wanting in contrast, that, though it did not wound the ear, it wearied it; when she had once recited two or three speeches, I could anticipate the manner of every succeeding one; it was like a long old legendary ballad of innumerable stanzas, everyone of which is sung to the same tune, eternally chiming in the ear without variation or relief. Mrs. Pritchard was an actress of a different cast, had more nature, and of course more change of tone, and variety both of action and expression: in my opinion the comparison was decidedly in her favour; but when after long and eager expectation I first beheld little Garrick, then young and light and alive in every muscle and in every feature, come bounding on the stage, and pointing at the wittol Altamont and heavy-paced Horatio—heavens, what a transition!—it seemed as if a whole century had been stept over in the transition of a single scene; old things were done away, and a new order at once brought forward, bright and luminous, and clearly destined to dispel the barbarisms and bigotry of a tasteless age, too long attached to the prejudices of custom, and superstitiously devoted to the illusions of imposing declamation. This heaven-born actor was then struggling to emancipate his audience from the slavery they were resigned to, and though at times he succeeded in throwing in some gleams of new born light upon them, yet in general they seemed to love darkness better than light, and in the dialogue of altercation between Horatio and Lothario bestowed far the greater show of hands upon the master of the old school than upon the founder of the new. I thank my stars, my feelings in these moments led me right; they were those of nature, and therefore could not err.

There is in Mr. Garrick's whole figure, movements, and propriety of demeanour something which I have met with rarely in the few Frenchmen I have seen and never, except in this instance, among the large number of Englishmen with whom I am acquainted. I mean in this context Frenchmen who have at least reached middle age; and, naturally, those moving in good society. For example, when he turns to some one with a bow, it is not merely that the head, the shoulders, the feet and arms, are engaged in this exercise, but that each member helps with great propriety to produce the demeanour most pleasing and appropriate to the occasion. When he steps on to the boards, even when not expressing fear, hope, suspicion, or any other passion, the eyes of all are immediately drawn to him alone; he moves to and fro among other players like a man among marionettes. From this no one, indeed, will recognize Mr. Garrick's ease of manner, who has never remarked the demeanour of a well-bred Frenchman, but, this being the case, this hint would be the best description. Perhaps the following will make the matter clearer. His stature is rather low than of middle height, and his body thickset. His limbs are in the most pleasing proportion, and the whole man is put together most charmingly. Even the eye of the connoisseur cannot remark any defect either in his limbs, in the manner they are knit, or in his movements. In the latter one is enchanted to observe the fullness of his strength, which, when shown to advantage, is more pleasing than extravagant gestures. With him there is no rampaging, gliding, or slouching, and where other players in the movements of their arms and legs allow themselves six inches or more scope in every direction farther than the canons of beauty would permit, he hits the mark with admirable certainty and firmness. It is therefore refreshing to see his manner of walking, shrugging his shoulders, putting his hands in his pockets, putting on his hat, now pulling it down over his eyes and then pushing it sideways off his forehead, all this with so slight a movement of his limbs as though each were his right hand. It gives one a sense of freedom and well-being to observe the strength and certainty of his movements and what complete command he has over the muscles of his body. I am convinced that his thickset form does much towards producing this effect. His shapely legs become gradually thinner from the powerful thighs downwards, until they end in the neatest foot you can imagine; in the same way his large arms taper into a little hand. How imposing the effect of this must be you can well imagine. But this strength is not merely illusory. He is really strong and amazingly dexterous and nimble. In the scene in The Alchemist where he boxes, he runs about and skips from one neat leg to the other with such admirable lightness that one would dare swear that he was floating in the air. In the dance in Much Ado about Nothing, also, he excels all the rest by the agility of his springs; when I saw him in this dance, the audience was so much delighted with it that they had the impudence to cry encore to their Roscius. In his face all can observe, without any great refinement of feature, the happy intellect in his unruffled brow, and the alert observer and wit in the lively eye, often bright with roguishness. His gestures are so clear and vivacious as to arouse in one similar emotions.

Hamlet appears in a black dress, the. only one in the whole court, alas! still worn for his poor father, who has been dead scarce a couple of months. Horatio and Marcellus, in uniform, are with him, and they are awaiting the ghost; Hamlet has folded his arms under his cloak and pulled his hat down over his eyes; it is a cold night and just twelve o'clock; the theatre is darkened, and the whole audience of some thousands are as quiet, and their faces as motionless, as though they were painted on the walls of the theatre; even from the farthest end of the playhouse one could hear a pin drop. Suddenly, as Hamlet moves towards the back of the stage slightly to the left and turns his back on the audience, Horatio starts, and saying: 'Look, my lord; it comes,' points to the right, where the ghost has already appeared and stands motionless, before anyone is aware of him. At these words Garrick turns sharply and at the same moment staggers back two or three paces with his knees giving way under him; his hat falls to the ground and both his arms, especially the left, are stretched out nearly to their full length, with the hands as high as his head, the right arm more bent and the hands lower, and the fingers apart; his mouth is open: thus, he stands rooted to the spot, with legs apart, but no loss of dignity, supported by his friends, who are better acquainted with the apparition and fear lest he should collapse. His whole demeanour is so expressive of terror that it made my flesh creep even before he began to speak. The almost terror-struck silence of the audience, which preceded this appearance and filled one with a sense of insecurity, probably did much to enhance this effect. At last he speaks, not at the beginning, but at the end of a breath, with a trembling voice: 'Angels and ministers of grace defend us!' words which supply anything this scene may lack and make it one of the greatest and most terrible which will ever be played on any stage. The ghost beckons to him; I wish you could see him, with eyes fixed on the ghost, though he is speaking to his companions, freeing himself from their restraining hands, as they warn him not to follow and hold him back. But at length, when they have tried his patience too far, he turns his face towards them, tears himself with great violence from their grasp, and draws his sword on them with a swiftness that makes one shudder, saying: 'By Heaven! I'll make a ghost; of him that lets me!' That is enough for them. Then he stands with his sword upon guard against the spectre, saying: 'Go on, I'll follow thee,' and the ghost goes off the stage. Hamlet still remains motionless, his sword held out so as to make him keep his distance, and at length, when the spectator can no longer see the ghost, he begins slowly to follow him, now standing still and then going on, with sword still upon guard, eyes fixed on the ghost, hair disordered, and out of breath, until he too is lost to sight. You can well imagine what loud applause accompanies this exit. It begins as soon as the ghost goes off the stage and lasts until Hamlet also disappears…

…Garrick plays Archer, a gentleman of quality disguised as a servant for reasons which may easily be guessed; and poor [Thomas] Weston takes the part of Scrub, a tapster in a wretched inn at which the former is lodging, and where all the wants of the stomach and the delights of the palate could be had yesterday, will be there on the morrow, but never today. Garrick wears a sky-blue livery, richly trimmed with sparkling silver, a dazzling beribboned hat with a red feather, displays a pair of calves gleaming with white silk, and a pair of quite incomparable buckles, and is, indeed, a charming fellow. And Weston, poor devil, oppressed by the burden of greasy tasks, which call him in ten different directions at once, forms an absolute contrast, in a miserable wig spoilt by the rain, a grey jacket, which had been cut perhaps thirty years ago to fit a better-fined paunch, red woollen stockings, and a green apron.… Garrick, sprightly, roguish, and handsome as an angel, his pretty little hat perched at a rakish angle over his bright face, walks on with firm and vigorous step, gaily and agreeably conscious of his fine calves and new suit, feeling himself head and shoulders taller beside the miserable Scrub. And Scrub, at the best of times a poor creature, seems to lose even such powers as he had and quakes in his shoes, being deeply sensible of the marked contrast between the tapster and the valet; with dropped jaw and eyes fixed in a kind of adoration, he follows all of Garrick's movements. Archer, who wishes to make use of' Scrub for his own purposes, soon becomes gracious, and they sit down together. An engraving has been made of this part of the scene, and Sayer has included a copy of it among his well-known little pictures. But it is not particularly like either Weston or Garrick, and of the latter, in especial, it is an abominable caricature, although there are in the same collection of pictures such excellent likenesses of him as Abel Drugger and Sir John Brute that they can scarce be surpassed. This scene should be witnessed by anyone who wishes to observe the irresistible power of contrast on the stage, when it is brought about by a perfect collaboration on the part of author and player, so that the whole fabric, whose beauty depends entirely on correct balance, be not upset, as usually happens. Garrick throws himself into a chair with his usual ease of demeanour, places his right arm on the back of Weston's chair, and leans towards him for a confidential talk; his magnificent livery is thrown back, and coat and man form one line of perfect beauty. Weston sits, as is fitting, in the middle of his chair, though rather far forward and with a hand on either knee, as motionless as a statue, with his roguish eyes fixed on Garrick. If his face expresses anything, it is an assumption of dignity, at odds with a paralysing sense of the terrible contrast And here I observed something about Weston which had an excellent effect. While Garrick sits there at his ease with an agreeable carelessness of demeanour, Weston attempts, with back stiff as a poker, to draw himself up to the other's height, partly for the sake of decorum, and partly in order to steal a glance now and then, when Garrick is looking the other way, so as to improve on his imitation of the latter's manner. When Archer at last with an easy gesture crosses his legs, Scrub tries to do the same, in which he eventually succeeds, though not without some help from his hands, and with eyes all the time either gaping or making furtive comparisons. And when Archer begins to stroke his magnificent silken calves, Weston tries to do the same with his miserable red woollen ones, but, thinking better of it, slowly pulls his green apron over them with an abjectness of demeanour, arousing pity in every breast. In this scene Weston almost excels Garrick by means of the foolish expression natural to him, and the simple demeanour that is apparent in all he says and does and which gains not a little from the habitual thickness of his tones, And this is, indeed, saying a great deal.

Sir John Brute is not merely a dissolute fel1ow, but Garrick makes him an old fop also, this being apparent from his costume. On top of a wig, which is more or less suitable for one of his years, he has perched a small, beribboned, modish hat so jauntily that it covers no more of his forehead than was already hidden by his wig. In his hands he holds one of those hooked oaken sticks, with which every young poltroon makes himself look like a devil of a fellow in the Park in the morning (as they call here the hours between 10 and 3). It is in fact a cudgel, showing only faint traces of art and culture, as is generally the case also with the lout who carries it. Sir John makes use of this stick to emphasize his words with bluster, especially when only females are present, or in his passion to rain blows where no one is standing who might take them amiss.…

Mr. Garrick plays the drunken Sir John in such a way that I should certainly have known him to be a most remarkable man, even if I had never heard anything of him and had seen him in one scene only in this play. At the beginning his wig is quite straight, so that his face is full and round. Then he comes home excessively drunk, and looks like the moon a few days before its last quarter, almost half his face being covered by his wig; the part that is still visible is, indeed, somewhat bloody and shining with perspiration, but has so extremely amiable an air to compensate for the loss of the other part. His waistcoat is open from top to bottom, his stockings full of wrinkles, with the garters hanging down, and, moreover—which is vastly strange—two kinds of garters; one would hardly be surprised, indeed, if he had picked up odd shoes. In this lamentable condition he enters the room where his wife is, and in answer to her anxious inquiries as to what is the matter with him (and she has good reason for inquiring), he, collecting his wits, answers: 'Wife, as well as a fish in the water'; he does not, however, move away from the doorpost, against which he leans as closely as if he wanted to rub his back. Then he again breaks into coarse talk, and suddenly becomes so wise and merry in his cups that the whole audience bursts into a tumult of applause. I was filled with amazement at the scene where he falls asleep. The way in which, with shut eyes, swimming head, and pallid cheeks, he quarrels with his wife, and, uttering a sound where 'r' and 'l' are blended, now appears to abuse her, and then to enunciate in thick tones moral precepts, to which he himself forms the most horrible contradiction; his manner, also, of moving his lips, so that one cannot tell whether he is chewing, tasting, or speaking: all this, in truth, as far exceeded my expectations as anything I have seen of this man. If you could but hear him articulate the word 'prerogative'; he never reaches the third syllable without two or three attempts.

As I paid much attention to Macklin's performances, and personally knew him, I shall endeavour to characterise his acting, and discriminate it from that of others. If Macklin really was of the old school, that school taught what was truth and nature. His acting was essentially manly—there was nothing of trick about it. His delivery was more level than modern speaking, but certainly more weighty, direct and emphatic. His features were rigid, his eye cold and colourless; yet the earnestness of his manner, and the sterling sense of his address, produced an effect in Shylock, that has remained to the present hour unrivalled. Macklin, for instance, in the trial scene, "stood like a tower," as Milton has it. He was "not bound to please" any body by his pleading; he claimed a right, grounded upon law, and thought himself as firm as the Rialto. To this remark it may be said, "You are here describing shylock:" True; I am describing Macklin. If this perfection be true of him, when speaking the language of Shakespeare, it is equally so, when he gave utterance to his own. Macklin was the author of Love à la Mode and the Man of the World. His performance of the two true born Scotsmen was so perfect, as though he had been created expressly to keep up the prejudice against Scotland. The late George Cooke was a noisy Sir Pertinax compared with Macklin. He talked of booing, but it was evident he took a credit for suppleness that was not in him. He was rather Sir Giles than Sir Pertinax. Macklin could inveigle as well as subdue; and modulated his voice, almost to his last year, with amazing skill.…

It has been commonly considered that Garrick introduced a mighty change in stage delivery: that actors had never, until his time, been natural. If Macklin at all resembled his masters, as it is probable he did, they can certainly not be obnoxious to a censure of. this kind. He abhorred all trick, all start and ingenious attitude; and his attacks upon Mr. Garrick were always directed to the restless abundance of his action and his gestures, by which, he said, rather than by the fair business of the character, he caught and detained all attention to himself.…

With respect to the alleged unfairness of Garrick in engrossing all attention to himself, a charge often repeated, it may, perhaps, be true, that this great master converged the interest of the whole too much about his particular character; and willingly dispensed with any rival attraction, not because he shunned competition with it as skill, but because it might encroach upon, delay or divide that palm for which he laboured—public applause.